Let’s begin with some dating advice (from the last person you should take dating advice from):

“Never settle” is nonsense. You should settle. As a matter of fact, you will settle.

I’m defining “settling” as the fear of committing to a romantic partner who falls short of your ideal.

However, the ideal partner does not exist. When we think about the traits we’d like to find in someone, no one is forcing us to compromise - as we ultimately will.

We invariably prefer indecision over committing ourselves to a single path because the future, which we dispose of to our liking, appears to us at the same time under a multitude of forms, equally attractive and equally possible.

-Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will

In Oliver Burkemann’s book Four Thousand Weeks, he nails the point:

Fantasy [ideal] romantic partners…can easily exhibit a range of characteristics that simply couldn’t coexist in one person in the real world. It’s common, for example, to enter a relationship unconsciously hoping that your partner will provide both an unlimited sense of stability and an unlimited sense of excitement – and then, when that’s not what transpires, to assume that the problem is your partner and that these qualities might coexist in someone else, whom you should therefore set off to find. The reality is that the demands are contradictory. The qualities that make someone a dependable source of excitement are generally the opposite of those that make him or her a dependable source of stability. Seeking both in one real human isn’t much less absurd than dreaming of a partner who’s both six and five feet tall.

Burkemann continues to describe a common theme in many relationship issues:

The cause of your difficulties isn’t that your partner is especially flawed, or that the two of your are especially incompatible, but that you’re finally noticing all the ways in which your partner is (inevitably) finite, and thus deeply disappointing by comparison with the world of your fantasy, where the limiting rules of reality don’t apply.

The phenomenon of avoiding commitment in the interest of keeping our options open (often to our own detriment) is not limited to dating. I see it clearly happening in other areas of life, namely with jobs and scheduling.

Stay on the fucking Bus

It’s become a trend that younger workers are staying at jobs for shorter durations. I can think of several friends who seem to have a new job every time I speak with them.

From a random article I found on a site called ResumeLab (?):

Generation Z has ignited a paradigm shift in the traditional concept of job stability, embracing a dynamic approach to their careers that often involves frequent job changes. Unlike their predecessors, they view job hopping not as a sign of instability but as a strategic means to diversify their skill sets, pursue new challenges, and seek environments that align with their values and ambitions.

First off - call me a boomer, but I would take the other side of that.

Diversification can be a good thing in many contexts, but not so much in this one. Phrases like “increasing diversification of skills” and “building optionality” seem great on the surface. Of course we want those things. But they come at the expense of the depth of knowledge, skills and experience gained when committing to a job for a longer duration.

While the term “job hopping” seems new and directly connected to Gen Z, this idea of prioritizing optionality is borne out of more common career advice.

From one of my favorite writers’ blogs titled, “The Optionality Fallacy”:

“We are obsessed with optionality. Not sure what to do with your life? Get a degree. Not quite sure what to do with this degree? Go to grad school. Still not quite sure? Get a consulting role at a big firm so you can decide what kind of job you enjoy. And so on and so forth. We fall prey to the optionality fallacy.

The problem is not with optionality itself. The problem is that we tend to assume optionality is built by keeping as many doors open for as long as possible. As Erik Torenberg puts it, it can be ‘like spending your whole life filling up the gas tank without ever driving.’

The versions of this I remember subscribing to most were:

Get A’s in high school so you have options of where to go to college.

Get a high GPA in college so you can have good job options.

These are not bad things to strive for by any means. The problem is that the implied goal is just maintaining optionality - which isn’t really a goal at all.

Similar to dating, we are fooled by this optionality fallacy. Then, one day we wake up to the realization that we are actually forced to settle for one occupation.

Once we realize that this first job is actually a pretty random topic area that rarely coincides with what we studied in college, there’s a misalignment of interests that leads to “trying something else” and job hopping to “diversify experience”. But by doing this, we’re opting against the patience and commitment required to reach the depth of expertise that will differentiate us in the marketplace.

The Finnish American photographer Arno Minkkinen dramatizes this deep truth about the power of patience with a parable about Helsinki’s main bus station. There are two dozen platforms there, he explains, with several different bus lines departing from each one – and for the first part of its journey, each bus leaving from any given platform takes the same route through the city as all the others, making identical stops. Think of each stop as representing one year of your career, Minkkinen advises photography students. You pick an artistic direction – perhaps you start working on platinum studies of nudes – and you begin to accumulate a portfolio of work. Three years (or bus stops) later, you proudly present it to the owner of a gallery. But you’re dismayed to be told that your pictures aren’t as original as you thought, because they look like knockoffs of the work of the photographer Irving Penn; Penn’s bus, it turns out, had been on the same route as yours. Annoyed at yourself for having wasted three years following somebody else’s path, you jump off that bus, hail a taxi, and return to where you started at the bus station. This time, you board a different bus, choosing a different genre of photography in which to specialize. But a few stops later, the same thing happens: you’re informed that your new body of work seems derivative, too. Back you go to the bus station. But the pattern keeps on repeating: nothing you produce ever gets recognized as being truly your own. What’s the solution? ‘It’s simple,’ Minkkinen says. ‘Stay on the bus. Stay on the fucking bus.’ A little farther out on their journeys through the city, Helsinki’s bus routes diverge, plunging off to unique destinations as they head through the suburbs and into the countryside beyond. That’s where the distinctive work begins. But it being at all only for those who can muster the patience to immerse themselves in the earlier stage–the trial-and-error phase of copying others, learning new skills, and accumulating experience”

The Problem with the “Maybe” Button

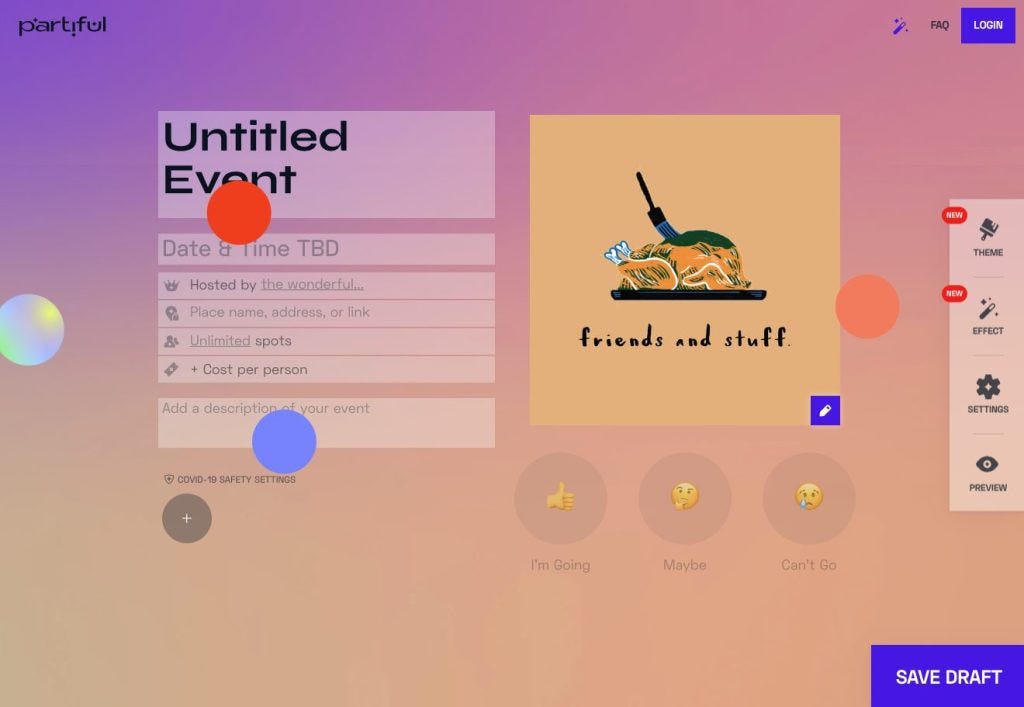

“I feel like a boomer what is this link?” -Anonymous subscriber’s response to a Partiful invitation

Partiful is a simple party planning website that streamlines event creation and invite tracking.

As a host, I’ve loved using the platform to customize event pages and quickly get something organized that I can send out to friends to put on their calendar and start tracking RSVPs.

After using it for the last year or two, I’ve become frustrated with it.

First, let’s rewind to the days before Partiful was released.

You invite someone to an event – manually (😱) – and your goal is to find out if they can make it or not. In an ideal world, this a binary choice: Yes or No.

However, managing schedules is complicated and involves layers of interdependencies. Sometimes we need time to figure it out.

Maybes take all kinds of shapes and sizes but can be bucketed into two categories:

There’s the genuine maybe – when people actually need time to sort out their schedule and intend to get back to you when they find out.

Then there’s the BS maybe. This is when people respond, “Sounds great, I’ll let you know” when you know damn well they have zero intention of coming. My theory is that these are borne out of people being afraid to disappoint or feeling like saying no is somehow a mean thing to do.

The problem is “Maybe” useless when organizing an event. Yes is great, no is worse, maybe is MUCH worse. When arranging space, food or just vibes, having an accurate headcount is everything. When you can’t get a good handle of headcount in advance, event organization becomes a guessing game. A shitty one.

More like a coin flip of:

Heads – you get your money back

Tails – you lose money because the restaurant just charged you a $200 no-show fee because your reservation is for 15 and only 10 showed up. Enjoy your meal!

Enter Partiful.

“Maybe” has now taken center stage. Almost positioned as the default option.

As an invitee, I originally loved this option – when you get invited to something you don’t actually want to go to and have very little intention of going to – great! Just click maybe. No need for commitment or direct communication.

Or you really would like to go, but there are plenty of other options going on that day that you also really would like to go to. Who cares! Just click maybe.

Probably good for Partiful’s engagement metrics – but bad for organizers.

Instead of picking a horse and saying no to the others, we take a page out of the dating thought pattern Oliver Burkeman described and we hang on to the illusion that we can do all of them.

In each of these areas - dating, careers and everyday scheduling - the real value comes when we pick an option and stick with it for a while.

We’re usually better off once we do.

Harvard University social psychologist Daniel Gilbert gave hundreds of people the opportunity to pick a free poster from a selection of art prints . Then he divided the participants into two groups. The first group was told that they had a month in which they could exchange their poster for any other one; the second group was told that the decision they’d already made had been final. In follow-up surveys, it was the latter group - those who were stuck with their decision, and who thus weren’t distracted by the thought that it might still be possible to make a better choice—who showed by far the greater appreciation for the work of art they’d selected.

Decisions and Revisions: The Affective Forecasting of Changeable Outcomes

The problem is that we genuinely believe we should maintain optionality at all costs. What if we miss out??

You come to realize that missing out on something —indeed, on almost everything—is basically guaranteed. Which isn’t actually a problem…because “missing out” is what makes our choices meaningful in the first place. Every decision to use a portion of time on anything represents the sacrifice of all the other ways in which you could have spent that time, but didn’t —and to willingly make that sacrifice is to take a stand, without reservation, on what matters most to you.

Take a stand, choose, commit and appreciate the joy of missing out.

The majority of this post was inspired by Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks. If I didn’t directly attribute a quote above, just assume it’s from the book. I absolutely loved it and I’d love to hear your thoughts on it. Let me know if you’d like to read it and I can lend you one of my copies.

https://x.com/lewmosey/status/1896131468960870490/photo/1

Great post!! Can I borrow your copy of 4000 weeks??? (: